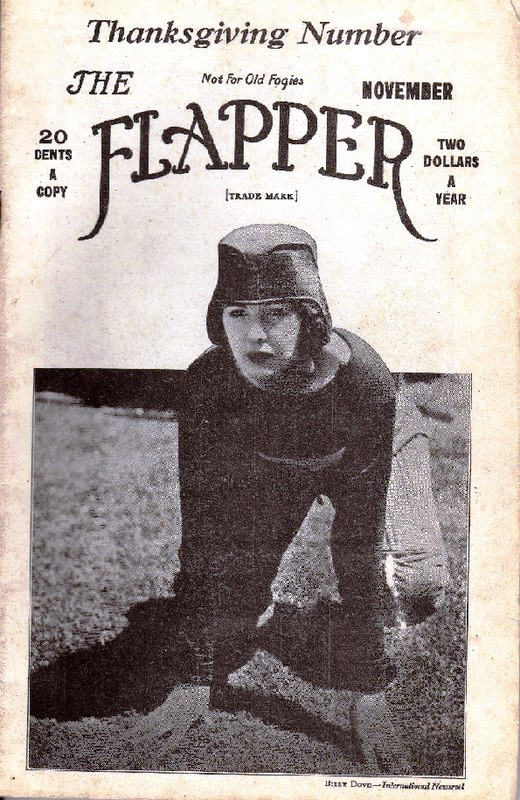

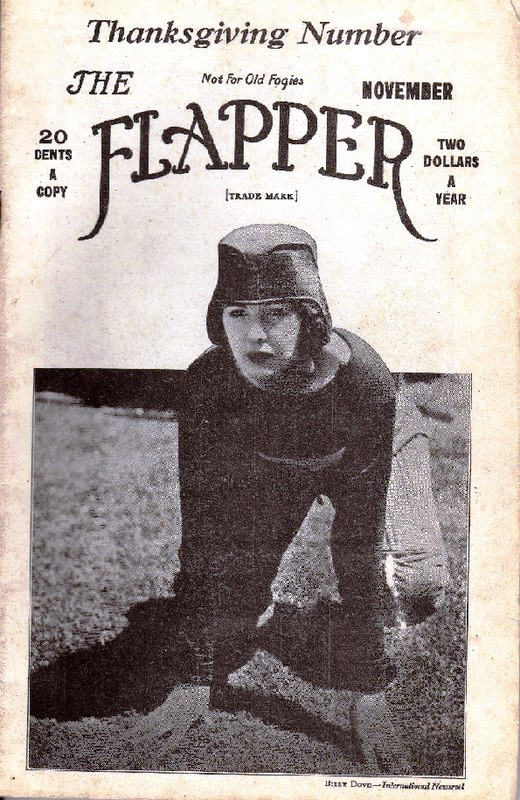

Jeanne LaMarr's fighting career, and indeed her life in general, is the apotheosis of the elusive nature of history. Detailing the life of a person from accounts nearing a century in the past can sometimes appear futile, especially when that life was purposefully vague. In the course of amassing a history of female fighters, one American fighter in particular, consistently eluded the type of pinning down that is the foundation of scholarly pursuit. Jeanne LaMarr. Was she a champion boxer or actress adroit at self-promotion? Was she French or American? The wife of an Italian Count or the abused spouse of an American? A murderer or the bereaved aunt (or perhaps mother?) of a suicide victim? The majority of the stories of LaMarr's life are a tribute to her skill at generating media interest in her life, and at insinuating that there may have been a few skeletons in her closet. In fact, there was most definitely one skeleton in her life, found on her property in 1938, that would embroil her in a scandal and FBI investigation and forever link her to death in addition to boxing.Jeanne's life and career contained a series of extravagant claims, and although many of them cannot be substantiated, it does not mean that they were not necessarily true. She claimed that she was European female welterweight champion, and records do indicate that she performed as a boxer in the circus and fair circuit in Europe in the first decade of the 1900s. Carnivals were where many sporting events, including boxing and wrestling, proliferated in the early 20th century, and although it may sound akin to profession, WWF-style wrestling to our modern sensibilities, at the time, carnivals and fairs hosted legitimate sporting events. Jeanne claims that during her in tenure in Europe, she knocked out twenty-five women and five men in her boxing bouts, but by the early 1920s, she immigrated to the United States. Perhaps she was just looking to showcase her skills in the land of opportunity or maybe her primary incentive was to leave the socially striated European continent behind her.The period between World War I and World War II was a tumultuous time, particularly in the war-ravaged Europe where the First World War devastated not only the landscape, but, in England in particular, the rigid social order established most recently by the Victorians and Edwardians. The structures that divided the aristocracy, the gentry, and the working class started to crumble, although older generations grasped at those social designations with wizened hands. The most prominent character to emerge from this period was "the modern girl," a sort of proto-type flapper who exemplified everything that was new in this post-world era. With short hair and a boyish figure, this girl was skilled in typically upper-class masculine pursuits, like race-car driving, dancing, golfing, and drinking American cocktails. Actress Billie Dove in a football uniform on the cover of "The Flapper," 1922 (Wikimedia Commons)The new girl featured in advertisements was the epitome of leisure who was pictured as being removed from rank and social hierarchy, although that was almost certainly not the case. The marketing of the new girl made it appear that anyone, regardless of social position, could live this luxurious and leisurely lifestyle exemplified in advertisements for cars and clothing. But these advertisements featuring 'the new girl' were marketing a lifestyle unattainable by most. The type of youth, male or female, who had the time to pursue sports, travel, dancing and drinking, was almost exclusively part of the aristocracy. And while the young British lords and ladies might make pretentious and feigned attempts to create distance from their titled and moneyed families, these social codes remained in place. The 1920s symbolize decadence, but not everyone could afford to gamble in exclusive clubs, purchase designer frocks, or drink expensive champagne. But the pursuit of sporting activities was one of the few elements of the upper-class lifestyle that did become part of nearly every level of the social strata. One may not be able to purchase a yacht, but he or she could certainly spend what leisure time he or she had to play tennis or go swimming.Trends were similar in the United States, where certain frivolities of the pre-war period ended, even in a landscape relatively unscathed by the horrors of the First World War. Scholar Marilyn Morgan describes the two images of the modern woman proliferated by magazines and featured in newspapers and popular fiction: the flapper and the athletic girl. While the flapper rebelled against social mores by drinking, smoking, dancing and bobbing her hair, she did not threaten traditional masculine authority because the type of girls who tried to follow this lifestyle needed money, which mean that flappers either had to come from wealth or they had to find it, typically through men. Female athletes, meanwhile, forever linked athleticism and strength to beauty, an innovative idea, given the previous preference for weak, pale women in the nineteenth century. While golf, tennis, and swimming were idealized as the appropriate sports for female athletes, boxing and wrestling remained on the fringes, practiced primarily by eccentrics or women who had no social status to lose.Jeanne LaMarr began her American career in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and according to an article found in the Women's Boxing archive, she was managed by Joe Woodman and George Lawrence. During a show featuring George Eagle and Young Tiger, Jeanne went three founds with bantamweight Bugs Moran. Interestingly, Jeanne is frequently described by contemporary accounts as being short, but she apparently fought as a welterweight at 145lbs (some modern bloggers claim Jeanne was 170lbs, but they are attributing the 'welterweight' description to the current MMA division weight range rather than the classic boxing weight class).Jeanne's moniker of 'Countess' was, she claimed, attributed to her royal status as the wife of an unnamed Italian Count, who she purportedly married in 1914. However, the Chicago Herald described Jeanne as the "Countess of Ten," indicating that her fight name came from her knocking her opponents down for a ten-count. Either way, the sobriquet of "Countess" was a fantastic fight name that, coupled with her French roots, added an air of mystique to Jeanne and her seemingly odd choice of career. Interestingly, Jeanne appears to have fought more men than women in her American fighting career. Jeanne asserted her own skill in the ring in 1925, when she declared to a judge (she was being arraigned for failing to keep a muzzle on her terrier) that she "knocked out twenty-five women and five men in Europe," but that no one would fight her in the United States." There was apparently a dearth of female opponents for Jeanne and according to a report in the Pittsburg Post Gazette, "she generally sparred with the young fellows who performed in Mr. Jafle's Friday evening amateur bouts."Sometime in 1927, Jeanne moved from the East Coast to sunny California, hoping again that she would be able to ignite her American boxing career. A 1927 announcement in The BillBoard, now known as Billboard Magazine, revealed that "pugilist" Jeanne LaMarr "rerouted her novelty act, providing for interludes by a dance team." The description of LaMarr as a novelty performer, written in an entertainment magazine, indicates that Jeanne may have been more of an actress than a pugilist. However, early 20th century fighting, including boxing and wrestling, often operated as part of the entertainment industry. Later that same year, Jeanne apparently married, which lends more credence to claims that her 'marriage' to the Italian Count was indeed fictitious. An article in the January 2, 1928, Chicago Tribune, identified her as the wife of Thomas Failace. Although the couple had only been married a few weeks, the marriage was a volatile one. The Tribune reported that police were called to their apartment after neighborhoods heard the sounds of "a woman being murdered." However, in the home they found Jeanne and Thomas apparently duking it out, engaging in a martial spat that escalated into a real boxing match.A 1936 article in the Miami News identified Jeanne as a French woman who participated in a three-round exhibition match with Herbert "Baby" Stribling. The paper claims that Jeanne "swore her mission in life was to place the women of the world on a level with men—by proving her right to be known as the world's champion lady fighter." The fight, however, was more comedic than a serious display of skill. Jeanne's second was a comedian named Michelena, who goofed off in her corner by 'accidently' catching his fingers in her hair, and imitating her opponent's corner by rubbing her legs, an indecent and inappropriate action at the time. Jeanne kicked him in the teeth, and later bashed him over the head with a stool when he attempted to douse her with water and wipe off her chest with a towel: a standard practice for male fighters, but insulting for this lady boxer. The 'Countess' then apparently tried to have her opponent arrested for striking a woman when he tapped her on the nose with his glove. The account in the Miami News indicated that Jeanne LaMarr's boxing career was a hoax, but another story in The Evening Independent claimed that while her title of Countess was fake, her boxing was real, although not necessarily in the ring. The paper revealed that Jeanne LaMarr knew how to defend herself: she once knocked out a bandit who tried to hold her up and scared off his cronies.Jeanne regularly visited gyms around the Los Angeles area, but according to the Pittsburg Post Gazette, Jeanne rarely found female opponents and thus earned her titled of "Woman's Champion of the World" by default. The paper does note that when unchallenged, yet again, at an event, Jeanne would seize the opportunity to belt out a "reasonably good" rendition of "La Marsellaise." Jeanne's fighting career was hindered, constantly, by the lack of opportunity to fight legitimate bouts, and that was not for her lack of tenacity. In 1933, Jeanne challenged Babe Didrikson, America's most famous woman athlete of the time, to a boxing match. Didrikson, however, was training to fight that other famous Babe, the great Bambino, Babe Ruth. The fight never happened between the Babes, nor did Didrickson ever fight Jeanne LaMarr. It seemed that LaMarr would never find the championship bout she desired, but she did find herself in the press, embroiled in a notorious case that would forever overshadow her fighting career.In late 1930s, Jeanne LaMarr was living as a semi recluse on her ranch home in San Bernadino, California, with a young man, Gustave Morgan van Herren, who she claimed was her nephew. Gustave apparently had a history of mental health issues, or, as the papers of the time described, he was "a mental case." Despite his health issues, aunt and nephew appeared to live happily, but in 1937, Gustave went missing after learning that a young lady he was in love with married another man. Neighbors later told reporters that Gustave was devastated by the loss of his lady love, and often spoke of suicide. Indeed, he had been previously hospitalized at the Stockton State Hospital for Mental Patients, and when he went missing, his aunt Jeanne insisted that he Gustave was being treated at a mental health hospital in New York. In 1938, a skeleton was found in a gully near her home and, as is the case anytime a body is discovered, pandemonium ensued.The skeleton, with a rifle by his side, was found by twenty-two-year-old William B. Jones, one of Jeanne's employees, on a Thursday. Jones had only begun working for Jeanne the previous Tuesday, and one of the first tasks Jeanne assigned to her new ranch hand was to "go out and hunt rabbits." Jones's inaugural rabbit-hunting expedition was marred by the finding of a partially-clothed skeleton lying in the sage brush with a .30/.30 caliber rifle pointing toward a skull punctured by what appeared to be the same caliber bullet. For reasons never fully elucidated, Jones waited until the following day to report his macabre discovery.Investigators ruled Gustave's death a suicide, but there were several unusual and suspicious circumstances that pointed to the self-proclaimed boxing champion.In the process of the investigation, detectives questioned Jeanne on several inconsistences in her story, the most pointed of which was whether she had opened his mail and pocketed any money contained in those epistles. Jeanne vehemently denied that she took any money, insisting that she had been her nephew's caretaker since he was five years old and that "talk of his having money is ridiculous." Any letters that she did open apparently had to do with the maintenance of his estate, whatever level of income Gustave may or may not have had. Jeanne took great umbrage to being questioned about her nephew's money and death, snapping, "If you suspect me of murder, why don't you charge me with it?" After the investigation, which local historians now claim was bungled, the death was ruled a clear suicide by the Los Angeles Sheriff's office.William Bright, Captain of the Los Angeles Sheriff's office, deemed Gustave's death a suicide, but that did not prevent Jeanne LaMarr's name from being smeared during the investigation. The papers pointed out that her title of countess was probably false, and constantly reiterated that fact by referring to her as "countess," with quotation marks. Her recent legal trouble was also revealed; she was arrested for drunk driving the day her nephew's body was found. But what truly started tongues wagging was the news that the FBI was already investigating Jeanne for being embroiled in a moral scandal. Several papers claimed that Jeanne was already under investigation by the District Attorney for some type of relationship with the young men working at a nearby Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. The CCC was a public relief camp for young men, so the insinuation was that the thirty-eight-year-old Jeanne had some inappropriate contact with these young men, most of them between the ages of 18 and 25. Despite Jeanne's distaste for police questioning, she took every opportunity when faced with the police or the press to discuss her former boxing career, often shadowboxing for the education of anyone in sight.There continues to be interest in the mysteries surrounding Jeanne LaMarr, which revolve not only around her boxing career and her murky antecedents, but, of course, her nephew's mysterious death. Local historians now claim that LaMarr drunkenly confessed to killing her nephew, keeping his fingers in a box (as a grisly keepsake?) and attempting to shoot poor William Jones when he discovered the skeleton. It is a delightfully macabre footnote to the story, but anecdotal evidence and hearsay are not enough to declare the Countess guilty. Jeanne's life may be best analyzed in the context of time. She pursued a career in a sport that, despite the enthusiasm for female athletes in the early 20th century, placed her firmly outside of the status quo. She was an anomaly, and rather than working to clarify any misconceptions about her marriages, her fight record, or her involvement in any illegal proceedings, Jeanne appeared to enjoy seeing the press puzzle over her story. Her enigmatic persona continues to incite conjecture in boxing enthusiasts, which, no doubt, she would gleefully, and perhaps ghoulishly, relish.

Actress Billie Dove in a football uniform on the cover of "The Flapper," 1922 (Wikimedia Commons)The new girl featured in advertisements was the epitome of leisure who was pictured as being removed from rank and social hierarchy, although that was almost certainly not the case. The marketing of the new girl made it appear that anyone, regardless of social position, could live this luxurious and leisurely lifestyle exemplified in advertisements for cars and clothing. But these advertisements featuring 'the new girl' were marketing a lifestyle unattainable by most. The type of youth, male or female, who had the time to pursue sports, travel, dancing and drinking, was almost exclusively part of the aristocracy. And while the young British lords and ladies might make pretentious and feigned attempts to create distance from their titled and moneyed families, these social codes remained in place. The 1920s symbolize decadence, but not everyone could afford to gamble in exclusive clubs, purchase designer frocks, or drink expensive champagne. But the pursuit of sporting activities was one of the few elements of the upper-class lifestyle that did become part of nearly every level of the social strata. One may not be able to purchase a yacht, but he or she could certainly spend what leisure time he or she had to play tennis or go swimming.Trends were similar in the United States, where certain frivolities of the pre-war period ended, even in a landscape relatively unscathed by the horrors of the First World War. Scholar Marilyn Morgan describes the two images of the modern woman proliferated by magazines and featured in newspapers and popular fiction: the flapper and the athletic girl. While the flapper rebelled against social mores by drinking, smoking, dancing and bobbing her hair, she did not threaten traditional masculine authority because the type of girls who tried to follow this lifestyle needed money, which mean that flappers either had to come from wealth or they had to find it, typically through men. Female athletes, meanwhile, forever linked athleticism and strength to beauty, an innovative idea, given the previous preference for weak, pale women in the nineteenth century. While golf, tennis, and swimming were idealized as the appropriate sports for female athletes, boxing and wrestling remained on the fringes, practiced primarily by eccentrics or women who had no social status to lose.Jeanne LaMarr began her American career in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and according to an article found in the Women's Boxing archive, she was managed by Joe Woodman and George Lawrence. During a show featuring George Eagle and Young Tiger, Jeanne went three founds with bantamweight Bugs Moran. Interestingly, Jeanne is frequently described by contemporary accounts as being short, but she apparently fought as a welterweight at 145lbs (some modern bloggers claim Jeanne was 170lbs, but they are attributing the 'welterweight' description to the current MMA division weight range rather than the classic boxing weight class).Jeanne's moniker of 'Countess' was, she claimed, attributed to her royal status as the wife of an unnamed Italian Count, who she purportedly married in 1914. However, the Chicago Herald described Jeanne as the "Countess of Ten," indicating that her fight name came from her knocking her opponents down for a ten-count. Either way, the sobriquet of "Countess" was a fantastic fight name that, coupled with her French roots, added an air of mystique to Jeanne and her seemingly odd choice of career. Interestingly, Jeanne appears to have fought more men than women in her American fighting career. Jeanne asserted her own skill in the ring in 1925, when she declared to a judge (she was being arraigned for failing to keep a muzzle on her terrier) that she "knocked out twenty-five women and five men in Europe," but that no one would fight her in the United States." There was apparently a dearth of female opponents for Jeanne and according to a report in the Pittsburg Post Gazette, "she generally sparred with the young fellows who performed in Mr. Jafle's Friday evening amateur bouts."Sometime in 1927, Jeanne moved from the East Coast to sunny California, hoping again that she would be able to ignite her American boxing career. A 1927 announcement in The BillBoard, now known as Billboard Magazine, revealed that "pugilist" Jeanne LaMarr "rerouted her novelty act, providing for interludes by a dance team." The description of LaMarr as a novelty performer, written in an entertainment magazine, indicates that Jeanne may have been more of an actress than a pugilist. However, early 20th century fighting, including boxing and wrestling, often operated as part of the entertainment industry. Later that same year, Jeanne apparently married, which lends more credence to claims that her 'marriage' to the Italian Count was indeed fictitious. An article in the January 2, 1928, Chicago Tribune, identified her as the wife of Thomas Failace. Although the couple had only been married a few weeks, the marriage was a volatile one. The Tribune reported that police were called to their apartment after neighborhoods heard the sounds of "a woman being murdered." However, in the home they found Jeanne and Thomas apparently duking it out, engaging in a martial spat that escalated into a real boxing match.A 1936 article in the Miami News identified Jeanne as a French woman who participated in a three-round exhibition match with Herbert "Baby" Stribling. The paper claims that Jeanne "swore her mission in life was to place the women of the world on a level with men—by proving her right to be known as the world's champion lady fighter." The fight, however, was more comedic than a serious display of skill. Jeanne's second was a comedian named Michelena, who goofed off in her corner by 'accidently' catching his fingers in her hair, and imitating her opponent's corner by rubbing her legs, an indecent and inappropriate action at the time. Jeanne kicked him in the teeth, and later bashed him over the head with a stool when he attempted to douse her with water and wipe off her chest with a towel: a standard practice for male fighters, but insulting for this lady boxer. The 'Countess' then apparently tried to have her opponent arrested for striking a woman when he tapped her on the nose with his glove. The account in the Miami News indicated that Jeanne LaMarr's boxing career was a hoax, but another story in The Evening Independent claimed that while her title of Countess was fake, her boxing was real, although not necessarily in the ring. The paper revealed that Jeanne LaMarr knew how to defend herself: she once knocked out a bandit who tried to hold her up and scared off his cronies.Jeanne regularly visited gyms around the Los Angeles area, but according to the Pittsburg Post Gazette, Jeanne rarely found female opponents and thus earned her titled of "Woman's Champion of the World" by default. The paper does note that when unchallenged, yet again, at an event, Jeanne would seize the opportunity to belt out a "reasonably good" rendition of "La Marsellaise." Jeanne's fighting career was hindered, constantly, by the lack of opportunity to fight legitimate bouts, and that was not for her lack of tenacity. In 1933, Jeanne challenged Babe Didrikson, America's most famous woman athlete of the time, to a boxing match. Didrikson, however, was training to fight that other famous Babe, the great Bambino, Babe Ruth. The fight never happened between the Babes, nor did Didrickson ever fight Jeanne LaMarr. It seemed that LaMarr would never find the championship bout she desired, but she did find herself in the press, embroiled in a notorious case that would forever overshadow her fighting career.In late 1930s, Jeanne LaMarr was living as a semi recluse on her ranch home in San Bernadino, California, with a young man, Gustave Morgan van Herren, who she claimed was her nephew. Gustave apparently had a history of mental health issues, or, as the papers of the time described, he was "a mental case." Despite his health issues, aunt and nephew appeared to live happily, but in 1937, Gustave went missing after learning that a young lady he was in love with married another man. Neighbors later told reporters that Gustave was devastated by the loss of his lady love, and often spoke of suicide. Indeed, he had been previously hospitalized at the Stockton State Hospital for Mental Patients, and when he went missing, his aunt Jeanne insisted that he Gustave was being treated at a mental health hospital in New York. In 1938, a skeleton was found in a gully near her home and, as is the case anytime a body is discovered, pandemonium ensued.The skeleton, with a rifle by his side, was found by twenty-two-year-old William B. Jones, one of Jeanne's employees, on a Thursday. Jones had only begun working for Jeanne the previous Tuesday, and one of the first tasks Jeanne assigned to her new ranch hand was to "go out and hunt rabbits." Jones's inaugural rabbit-hunting expedition was marred by the finding of a partially-clothed skeleton lying in the sage brush with a .30/.30 caliber rifle pointing toward a skull punctured by what appeared to be the same caliber bullet. For reasons never fully elucidated, Jones waited until the following day to report his macabre discovery.Investigators ruled Gustave's death a suicide, but there were several unusual and suspicious circumstances that pointed to the self-proclaimed boxing champion.In the process of the investigation, detectives questioned Jeanne on several inconsistences in her story, the most pointed of which was whether she had opened his mail and pocketed any money contained in those epistles. Jeanne vehemently denied that she took any money, insisting that she had been her nephew's caretaker since he was five years old and that "talk of his having money is ridiculous." Any letters that she did open apparently had to do with the maintenance of his estate, whatever level of income Gustave may or may not have had. Jeanne took great umbrage to being questioned about her nephew's money and death, snapping, "If you suspect me of murder, why don't you charge me with it?" After the investigation, which local historians now claim was bungled, the death was ruled a clear suicide by the Los Angeles Sheriff's office.William Bright, Captain of the Los Angeles Sheriff's office, deemed Gustave's death a suicide, but that did not prevent Jeanne LaMarr's name from being smeared during the investigation. The papers pointed out that her title of countess was probably false, and constantly reiterated that fact by referring to her as "countess," with quotation marks. Her recent legal trouble was also revealed; she was arrested for drunk driving the day her nephew's body was found. But what truly started tongues wagging was the news that the FBI was already investigating Jeanne for being embroiled in a moral scandal. Several papers claimed that Jeanne was already under investigation by the District Attorney for some type of relationship with the young men working at a nearby Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. The CCC was a public relief camp for young men, so the insinuation was that the thirty-eight-year-old Jeanne had some inappropriate contact with these young men, most of them between the ages of 18 and 25. Despite Jeanne's distaste for police questioning, she took every opportunity when faced with the police or the press to discuss her former boxing career, often shadowboxing for the education of anyone in sight.There continues to be interest in the mysteries surrounding Jeanne LaMarr, which revolve not only around her boxing career and her murky antecedents, but, of course, her nephew's mysterious death. Local historians now claim that LaMarr drunkenly confessed to killing her nephew, keeping his fingers in a box (as a grisly keepsake?) and attempting to shoot poor William Jones when he discovered the skeleton. It is a delightfully macabre footnote to the story, but anecdotal evidence and hearsay are not enough to declare the Countess guilty. Jeanne's life may be best analyzed in the context of time. She pursued a career in a sport that, despite the enthusiasm for female athletes in the early 20th century, placed her firmly outside of the status quo. She was an anomaly, and rather than working to clarify any misconceptions about her marriages, her fight record, or her involvement in any illegal proceedings, Jeanne appeared to enjoy seeing the press puzzle over her story. Her enigmatic persona continues to incite conjecture in boxing enthusiasts, which, no doubt, she would gleefully, and perhaps ghoulishly, relish.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement