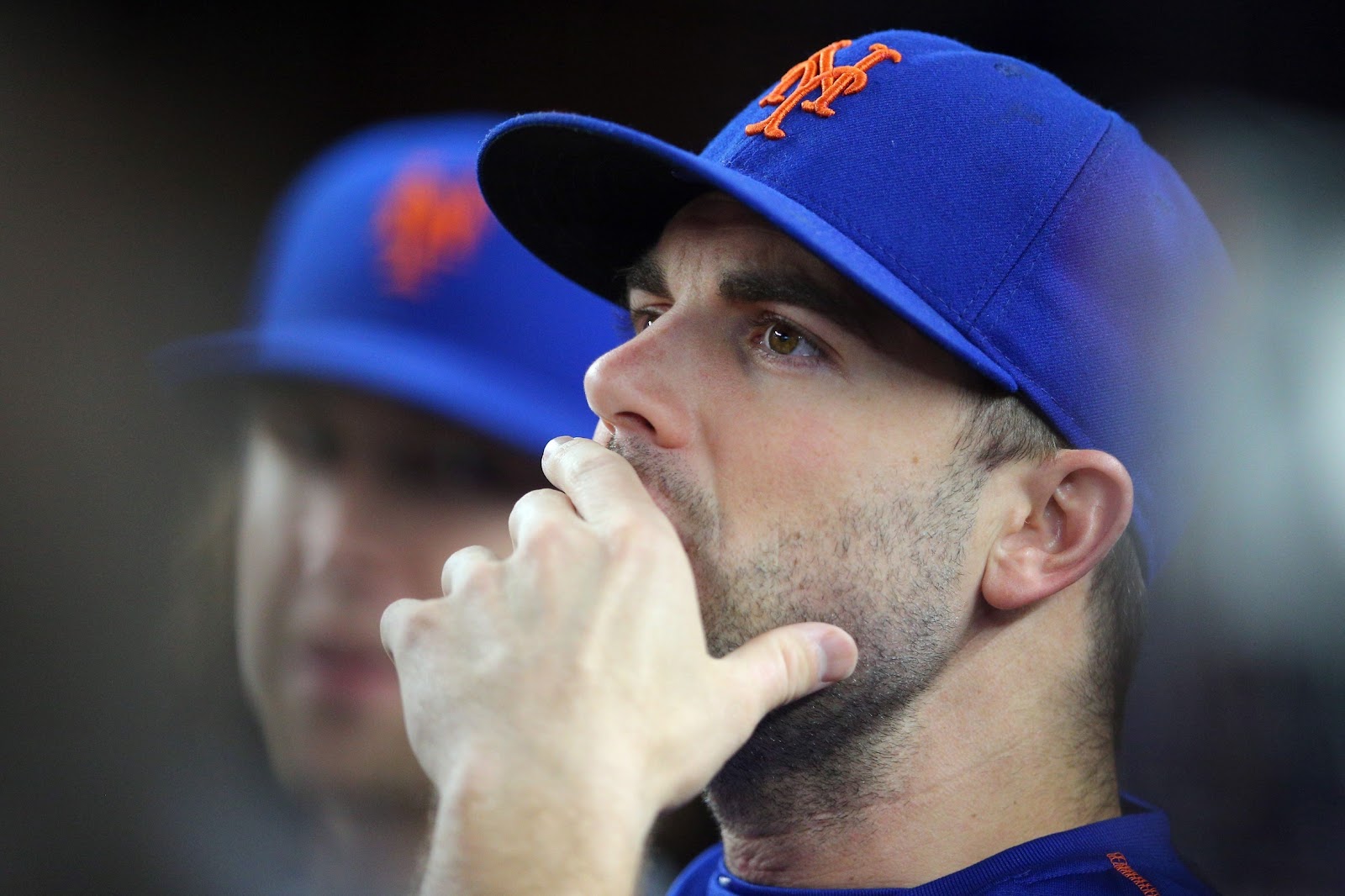

Photo by Anthony Gruppuso-USA TODAY Sports

David Wright waited 12 seasons and nearly eight hours to hit his first World Series home run. The dozen years in the wilderness you know about. There was a visit to the postseason in 2006, his third season, when Wright was one of the best young hitters in baseball and his New York Mets looked like an ascendant National League power; they ran into an infuriating kismet-kissed St. Louis Cardinals team in the NLCS, and wound up the second-to-last victims of a championship squad that won 82 games during the regular season. It's baseball. It happens.And then there was a decade during which Wright continued to play—every day and extremely hard and generally very well—for Mets teams that lapsed tragically into metaphor. They were bad, which is a thing that happens to baseball teams, but they were bad in unconscionable parallel with other bigger, broader badnesses. There was gilded, giddy bloat and collapse in 2007 and 2008; a broke-ass bottoming-out in the years that followed; ongoing false hope and the slow-motion revelation of the faithlessness and foolishness of those in charge; and a whole a lot of echoing meaningless games against the Miami Marlins. The team became a sort of hospice ward for recognizable players on their way out of the majors, men who wished to play their last games in peace, or anyway in front of rustling crowds of masochists. There was an Omir Santos T-shirt giveaway. During the nine seasons between Mets postseason games, David Wright was an All-Star six times, which was basically every season in which he was healthy enough to be selected.Wright's process involves a great deal of stretching and treatment designed to minimize the discomfort caused by the series of increasingly debilitating injuries that descend in a causal chain from the spinal stenosis that will eventually end his career. Wright's problems with his neck, and now with his shoulder, all owe to him attempting to compensate for the painful and constricting narrowing of his spine, and each new workaround opens new avenues to new hardships. Wright is not playing in Mets spring training games yet, because he cannot currently throw a baseball. Sooner or later, it is going to be too much, or enough.Wright didn't want to talk about any of this after Game 3, which was the only game the Mets would win in that World Series. "No one's complaining," he said. "It's the World Series." He was happier to talk about the home run he hit in the first inning, which left his bat at 103 miles per hour and caused the stadium to levitate for a full 90 seconds. He imitated the sound of the crowd. His eyes hit some happy spot in the middle distance. "Running around the bases," he said, "it's like you're floating." This is the sort of thing that baseball players say, and David Wright does not seem like the type to tell a lie. Because it is the sort of thing that baseball players say, it is the sort of thing that someone writing about baseball would try not to write; it's redundant, for one thing, but also there are some things best left described by the people that have been blessed to experience them. I can tell you what it felt like for me to see that moment, boiling away in the auxiliary press box, pretending to be professional and watching the terrycloth dandruff spun off the towels that the team distributed to fans drift through the air like confetti. I can tell you what it sounded like, how the delirious jet-engine howling above and below was turned tinny and distant and strange by the concrete and Plexiglas that encased the climate-controlled tank; I can tell you about the stadium stirring and shivering as the shared sense of surprise in it started to rise into something like belief. That was the part of it that was for me.But I can also tell you that floating around the bases was just what I wanted for David Wright, just the sort of reward that he'd earned after all those years of service in the dirt. He grew up a Mets fan, in Virginia, which means he had to know what it would mean for his specific dream to come true; there is always a way for things to go wrong, because baseball is like that and because the Mets are really like that. And so when the Mets fan lived that fantasy, vaporized a home run in a World Series win and was then borne aloft around the bases by the happy fury thrown off by fans experiencing something like the same thing, it was both sweet and edged with something sadder. The monkey's paw had already curled, the twist was already at work in his back, squeezing hard on the time left. This was probably always the deal: if you get what you want, you do not get to hold it; by the time you touch it, you are almost gone. Baseball is like that, and other things are also like that.Earlier this week in the New York Post, Joel Sherman talked to Don Mattingly, who was the New York Yankees' answer to Wright during a low ebb for their franchise a couple decades ago. While the team was riven by dysfunction and dopiness, Mattingly was reliably one of the best hitters in baseball; by the time the team started to figure things out, during the brief executive exile of their ulcerous owner, Mattingly was already in decline. Like Wright, Mattingly had back problems, and cycled through various new routines and treatments; his pre-game routines stretched longer and longer, and only led back to the most rudimentary baseline. Mattingly was finished at the age of 34; he didn't officially retire at the end of the 1995 season, but did realize at the end of another offseason of work that he just didn't want to do it anymore. "The mental side began to wear me down," Mattingly told Sherman. "You have to do all of this just to be OK, and you really are not what you used to be and it just is not as much fun."Wright is 34, but not yet at the point Mattingly reached at the end. He is going to work around the impingements and negotiate the various switchbacks that his body is going to throw at him, and he's going to do his best to play; he still is not complaining. The Mets seem inclined to let him continue to fight for as long as he is willing to do it; they owe him as much, and besides, they're letting him do it because he's still one of their best players when healthy. This all only ever goes one way, but there are various different ways it can go, and no set time for the moment when it's gone. Wright will choose, right up until the moment that there is no longer a choice to make. This has been clear for some time, now.It is not a complicated choice. Baseball is David Wright's job, and right now it is transparently a grind, but it is also a game. The specifics of that balance is another thing that players and the rest of us might understand differently, but it's also something that anyone who has ever loved anything can understand. There are things powerful enough to pick us up, that can carry us from here to there; we float and we know that we do so is in defiance of some old and stubborn laws, but also and more urgently we are nevertheless aloft, all the way off the ground, in defiance and in delight and in awe. You wouldn't give that up, either.Want to read more stories like this from VICE Sports? Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

This is the sort of thing that baseball players say, and David Wright does not seem like the type to tell a lie. Because it is the sort of thing that baseball players say, it is the sort of thing that someone writing about baseball would try not to write; it's redundant, for one thing, but also there are some things best left described by the people that have been blessed to experience them. I can tell you what it felt like for me to see that moment, boiling away in the auxiliary press box, pretending to be professional and watching the terrycloth dandruff spun off the towels that the team distributed to fans drift through the air like confetti. I can tell you what it sounded like, how the delirious jet-engine howling above and below was turned tinny and distant and strange by the concrete and Plexiglas that encased the climate-controlled tank; I can tell you about the stadium stirring and shivering as the shared sense of surprise in it started to rise into something like belief. That was the part of it that was for me.But I can also tell you that floating around the bases was just what I wanted for David Wright, just the sort of reward that he'd earned after all those years of service in the dirt. He grew up a Mets fan, in Virginia, which means he had to know what it would mean for his specific dream to come true; there is always a way for things to go wrong, because baseball is like that and because the Mets are really like that. And so when the Mets fan lived that fantasy, vaporized a home run in a World Series win and was then borne aloft around the bases by the happy fury thrown off by fans experiencing something like the same thing, it was both sweet and edged with something sadder. The monkey's paw had already curled, the twist was already at work in his back, squeezing hard on the time left. This was probably always the deal: if you get what you want, you do not get to hold it; by the time you touch it, you are almost gone. Baseball is like that, and other things are also like that.Earlier this week in the New York Post, Joel Sherman talked to Don Mattingly, who was the New York Yankees' answer to Wright during a low ebb for their franchise a couple decades ago. While the team was riven by dysfunction and dopiness, Mattingly was reliably one of the best hitters in baseball; by the time the team started to figure things out, during the brief executive exile of their ulcerous owner, Mattingly was already in decline. Like Wright, Mattingly had back problems, and cycled through various new routines and treatments; his pre-game routines stretched longer and longer, and only led back to the most rudimentary baseline. Mattingly was finished at the age of 34; he didn't officially retire at the end of the 1995 season, but did realize at the end of another offseason of work that he just didn't want to do it anymore. "The mental side began to wear me down," Mattingly told Sherman. "You have to do all of this just to be OK, and you really are not what you used to be and it just is not as much fun."Wright is 34, but not yet at the point Mattingly reached at the end. He is going to work around the impingements and negotiate the various switchbacks that his body is going to throw at him, and he's going to do his best to play; he still is not complaining. The Mets seem inclined to let him continue to fight for as long as he is willing to do it; they owe him as much, and besides, they're letting him do it because he's still one of their best players when healthy. This all only ever goes one way, but there are various different ways it can go, and no set time for the moment when it's gone. Wright will choose, right up until the moment that there is no longer a choice to make. This has been clear for some time, now.It is not a complicated choice. Baseball is David Wright's job, and right now it is transparently a grind, but it is also a game. The specifics of that balance is another thing that players and the rest of us might understand differently, but it's also something that anyone who has ever loved anything can understand. There are things powerful enough to pick us up, that can carry us from here to there; we float and we know that we do so is in defiance of some old and stubborn laws, but also and more urgently we are nevertheless aloft, all the way off the ground, in defiance and in delight and in awe. You wouldn't give that up, either.Want to read more stories like this from VICE Sports? Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

Advertisement

That was the longer part of the wait. The last eight hours or so began before noon on the day of Game 3 of the 2015 World Series, when Wright arrived at Citi Field to begin going through the long process of preparing himself to play in a baseball game that would start at 8:08 PM. Sterling, who carves filet mignon at the Pat LaFrieda steak sandwich station in left center and who I talked to much later that night, told me that Wright beat the concession workers to the stadium by over an hour. This was not some aggrandized act of leadership-by-example try-hardery on Wright's part. There was no reason to be at the stadium that early, except for the fact that it now took Wright roughly that long to get ready for every game.Read More: Let's Work Together To Find The Best Alternate Term For Home Run

Advertisement

Advertisement