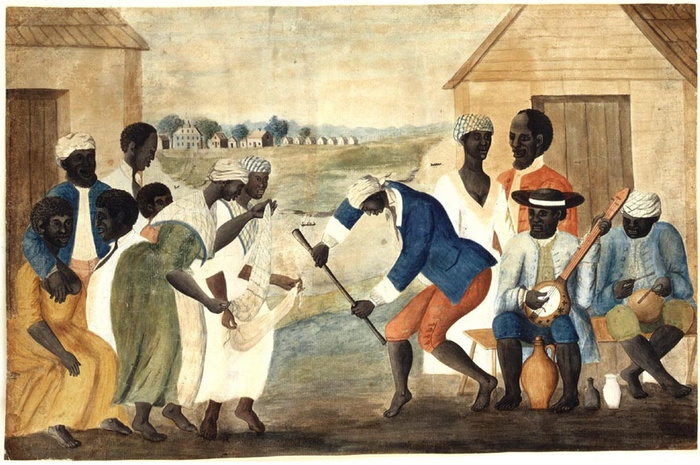

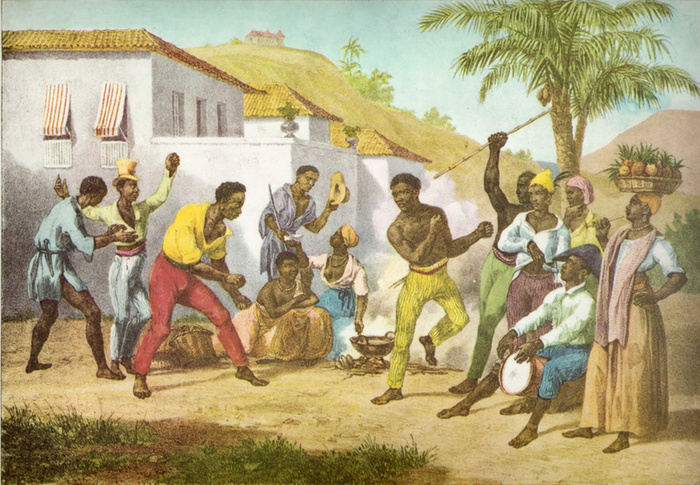

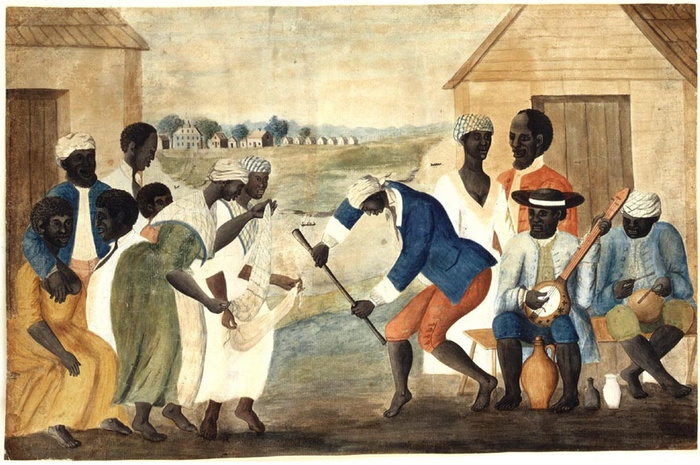

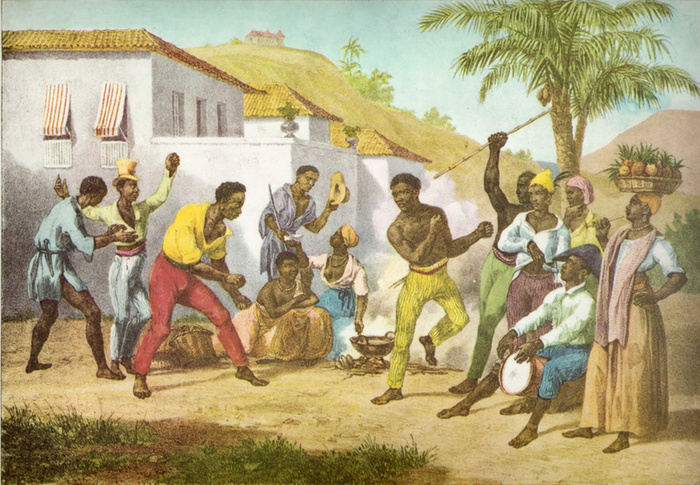

The horrors of slavery in America cannot be understated, nor can the irreparable damage to a culture be something that is ignored or brushed aside. The men, women, and children who were sold, against their will, and taken across the vast ocean to a new world, only to be starved, worked to the bone, assaulted, and killed. There is no space to excuse slavery, or to talk about plantations where slaves were 'treated well,' because without the right of autonomy, a person cannot be free. Certainly there were other groups in the young United States who lived in abject poverty and whose existence was terrible, but it is inappropriate to attempt an equivalence between the life of a poor white man and the reality of an African slave, who was roundly dehumanized and demoralized for the benefit of white upper and middle class society.The atrocities perpetrated upon the enslaved African community are so vast and so varied that one article cannot suffice to explore them adequately. This article, instead, focusing on how the Middle Passage did not completely destroy the culture, the history, the practices, the customs, the traditions of the African men, women, and children who were enslaved. History books frequently reduce the lives of slaves to hollow experiences, focusing on dates and wars, and ignoring the everyday life of the men, women, and children who lived as slaves in the United States.But it would be another form of erasure if we did not recognize the significant impact that the wide range of African traditions had upon American culture. Each person brought with him or her customs of food, music, art, and dance specific to their community, creating an amalgam of traditions that would eventually be reduced to that of a singular representation of Africanism. Despite the horror of slavery, many of the newly imported African slaves were able to retain aspects of their culture and pass it down through the generations, creating a new creole community with shared, if varied, traditions and customs.In Fighting for Honor, African scholar T.J. Desch Obi reveals that slave routes did not randomly distribute Africans, but rather "the combination of trading patterns and preferences of European planters in the Americas for laborers of specific African ethnicities tended to lump together large numbers of captive Africans from certain areas into particular colonies in the Americas." Therefore, there might be a large majority of slaves from a specific community or tribe ensconced in a particular plantation. The concentration of slaves from a shared background aided in the collective remembrance of their culture's beliefs and practices.In South Carolina there was an influx of slaves imported from Central Africa who brought with them their own martial arts traditions. Out of this amalgamous collective of various communities and tribes, the art of "Kicking and Knocking" was born—a fighting sport that consisted of kicks, strikes, and head butting. Desch Obi argues that the style of fighting most often employed and practiced by African slaves, wrestling and the art of 'Kicking and Knocking,' had greater utility for that population than traditional English boxing. The Angolan practice of head butting became the 'knocking' in this new composite style, where fighters would either head-butt as part of the larger 'Kicking and Knocking' style or isolate that attack by grabbing each other by the ears and slamming their heads together until one of the fighters submitted. The knock of 'Kicking and Knocking' is purportedly from the sound that the fighters' heads made when they crashed into each other. Kicking, meanwhile, grew, in part, from the engolo tradition of foot sweeps and high inverted kicks. 'Kicking and Knocking' was practiced as either sport or ritual dance, but both techniques, along with wrestling, could be used in be hidden in ceremonial dance and in basic defense against rivals, slave hunters, or foreman. In a 1938 interview with the Federal Writers' 'Slave Narrative Project,' former slave Will Adams, remembered some of his experiences growing up on a Texas plantation. During Christmas, the plantation owner would host a large party where the slaves, for once, were able to have their fill of food and drink. Adams recalled that the master would instruct two of the slaves to wrestle each other, saying that "our sports and dances was big sport for the white folks." Mr. Adams went on to explain that the slaves not only fought each other, they fought white men, too. "en slav'ry time grown white boys woud come tuh play en wrassle wid de "Niggers" Sho' woud."African wrestling in enslaved populations came from a variety of traditions, including the Nigerian of mgba and the Sengalese art of laamb, and often featured leg-wrapping techniques, which marked its distinction from the collar-and-elbow practiced by the growing Irish immigrant population in the U.S. African 'wrasslin' took the form of sport and play, and in many circumstances, slaves would wrestle each other to, as Frederick Douglas wrote, "win laurels" and display their physical prowess to young women in the audience. Douglas noted that sports were encouraged by plantation owners, including wrestling and boxing, which Douglas deemed "wild and low sports peculiar to semi-civilized people," but that "rational enjoyment" was not. Douglas felt that by encouraging the slaves the participate in 'low' sports, there would not be room for them to explore more important pursuits, such as reading, writing, or perhaps, planning a rebellion. He explained that plantation owners encouraged fighting because it was "among the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection."

In a 1938 interview with the Federal Writers' 'Slave Narrative Project,' former slave Will Adams, remembered some of his experiences growing up on a Texas plantation. During Christmas, the plantation owner would host a large party where the slaves, for once, were able to have their fill of food and drink. Adams recalled that the master would instruct two of the slaves to wrestle each other, saying that "our sports and dances was big sport for the white folks." Mr. Adams went on to explain that the slaves not only fought each other, they fought white men, too. "en slav'ry time grown white boys woud come tuh play en wrassle wid de "Niggers" Sho' woud."African wrestling in enslaved populations came from a variety of traditions, including the Nigerian of mgba and the Sengalese art of laamb, and often featured leg-wrapping techniques, which marked its distinction from the collar-and-elbow practiced by the growing Irish immigrant population in the U.S. African 'wrasslin' took the form of sport and play, and in many circumstances, slaves would wrestle each other to, as Frederick Douglas wrote, "win laurels" and display their physical prowess to young women in the audience. Douglas noted that sports were encouraged by plantation owners, including wrestling and boxing, which Douglas deemed "wild and low sports peculiar to semi-civilized people," but that "rational enjoyment" was not. Douglas felt that by encouraging the slaves the participate in 'low' sports, there would not be room for them to explore more important pursuits, such as reading, writing, or perhaps, planning a rebellion. He explained that plantation owners encouraged fighting because it was "among the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection." While African slaves brought their martial arts traditions with them, the South was becoming enamored with boxing. In the early eighteenth century, wealthy families would send their sons to England and other parts of Europe for their educations. Although young men from the North and the South made the journey to England, the vast majority of them were Southern, due in most part to the surplus of wealth found in that plantation-rich part of the country. The young men would be schooled in academics, art, and culture, of course, and would typically sow their wild oats amidst the vast cultural diversions of the old country. British pugilism, at the time, was just entering that Golden Age of fighting, when the working-class and the elite both pursued the sweet science. Young American men of a certain personality type learned to box from British pugilism instructors and took their knowledge back with them to the more puritanical America. But they found their choice of opponents was lacking. They turned to a seemingly abundant source of punching bags—or so they thought. If the young Southern gentleman thought that they would find easy targets in the men they kept enslaved, they were very wrong.There is a great deal of conjecture as to just how prolific and violent boxing matches were on plantations. To a certain extent, it did not make sense, economically, for plantation owners to put their slaves up for brutal fights that could, ostensibly, damage the slave or reduce his ability to do work. Some historians argue unilaterally that these types of fights a la Django Unchained did not take place. However, there are anecdotal accounts of brawls between slaves, of matches were slaves were forced to fight each other to the death for a chance at freedom. These accounts may be unsubstantiated, but that does not mean that they did not occur. After all, it would not have been in the best interest of slave owners to promote these fights in any type of publication, nor would it have been wise for written accounts to get in the hands of abolitionists.Desch Obi recognizes two forms of contests in the Antebellum South: matches between slaves on the same plantation for 'fun' and matches between slaves from different plantations for the purpose of gambling. According to an account from former slave turned abolitionist Henry Bibb, the fights were not in the of English prizefighting but rather in the 'Kicking and Knocking,' reducing, to a certain extent, the damage upon each of the participant. It is undeniable that slaves boxed and wrestled each other, but given the circumstances, it is not likely that they fought to the death, or to the maiming or disfiguring of their opponent, frequently. But African slaves certainly fought each other and often fought white men as well. Sometimes, they fought the very men who enslaved them.

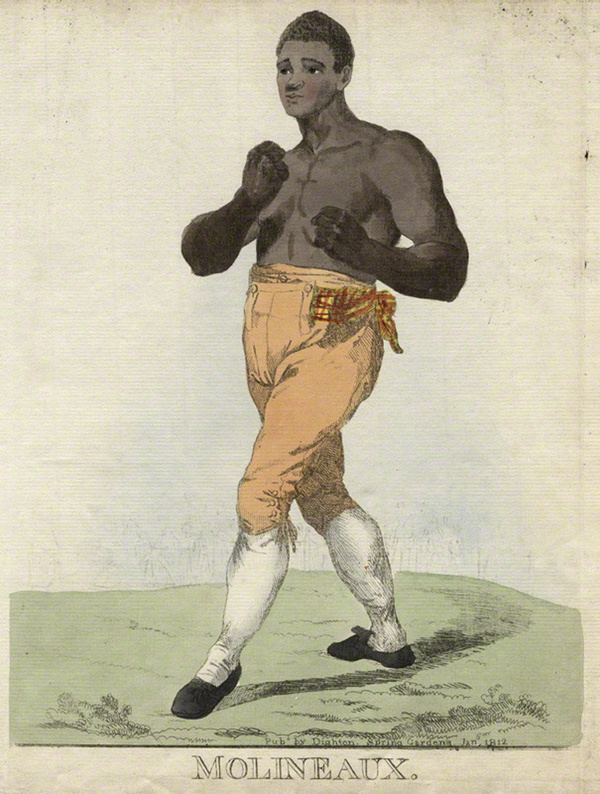

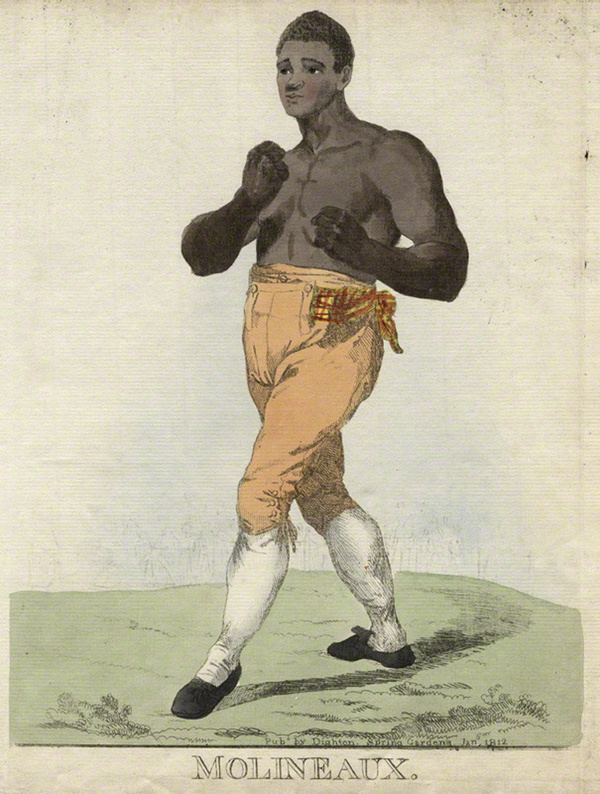

While African slaves brought their martial arts traditions with them, the South was becoming enamored with boxing. In the early eighteenth century, wealthy families would send their sons to England and other parts of Europe for their educations. Although young men from the North and the South made the journey to England, the vast majority of them were Southern, due in most part to the surplus of wealth found in that plantation-rich part of the country. The young men would be schooled in academics, art, and culture, of course, and would typically sow their wild oats amidst the vast cultural diversions of the old country. British pugilism, at the time, was just entering that Golden Age of fighting, when the working-class and the elite both pursued the sweet science. Young American men of a certain personality type learned to box from British pugilism instructors and took their knowledge back with them to the more puritanical America. But they found their choice of opponents was lacking. They turned to a seemingly abundant source of punching bags—or so they thought. If the young Southern gentleman thought that they would find easy targets in the men they kept enslaved, they were very wrong.There is a great deal of conjecture as to just how prolific and violent boxing matches were on plantations. To a certain extent, it did not make sense, economically, for plantation owners to put their slaves up for brutal fights that could, ostensibly, damage the slave or reduce his ability to do work. Some historians argue unilaterally that these types of fights a la Django Unchained did not take place. However, there are anecdotal accounts of brawls between slaves, of matches were slaves were forced to fight each other to the death for a chance at freedom. These accounts may be unsubstantiated, but that does not mean that they did not occur. After all, it would not have been in the best interest of slave owners to promote these fights in any type of publication, nor would it have been wise for written accounts to get in the hands of abolitionists.Desch Obi recognizes two forms of contests in the Antebellum South: matches between slaves on the same plantation for 'fun' and matches between slaves from different plantations for the purpose of gambling. According to an account from former slave turned abolitionist Henry Bibb, the fights were not in the of English prizefighting but rather in the 'Kicking and Knocking,' reducing, to a certain extent, the damage upon each of the participant. It is undeniable that slaves boxed and wrestled each other, but given the circumstances, it is not likely that they fought to the death, or to the maiming or disfiguring of their opponent, frequently. But African slaves certainly fought each other and often fought white men as well. Sometimes, they fought the very men who enslaved them. The slaves who did fight in the of English pugilism, especially in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, may have had more opportunity to change their circumstances, but the United States, even in the North, was not the ideal place for them to showcase their talents. As was revealed in last week's article on the Irish, Jewish, and African immigrant populations in England, African men had opportunities to fight and create careers for themselves in Britain, and so the few African American pugilists who succeeded in the U.S. found ways to move to England. Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux were both born slaves and after becoming free, moved to New York and then to England. It is unclear in the records just how both men went from slaves to freeman, despite conjecture that they earned it via their pugilistic endeavors. Richmond was a freeman before he was employed by the Duke of Northumberland and taken to England with his new master to work, on his own, as a cabinetmaker and a boxer. There are legends, completely unsubstantiated and embellished over time, that claim Molineaux won his freedom after his master won $100,000 in a bet on Tom's success, and a version of this could be true. The most important takeaway from both Richmond and Molineaux stories is that despite their dominance as pugilists in the United States, given the opportunity, they left as soon as they could for better lives in England. Even when African men and women were technically free in the United States, their lives were still harsh and tainted by racism and hatred in the country that neither they, nor their ancestors, would have chosen for their own.African boxers were not the only ones to set sail for England. White American pugilists also saw England as the preeminent location for aspiring champions and their departure, along with African fighters, left the United States bereft of some of the best talent. Meanwhile, those men and women still enslaved in the South sought to create their own fighting traditions, carved out of the customs of their ancestors. Fighting sports in enslaved populations in the United States functioned as ritual, as performance, and as communal bonding. The continuation of African traditions in their current, dire circumstances provided the African men and women with a chance to remember their history through song, dance, and sport.Certain fighting sports in the South were, interestingly, more of a creation of new, brutal forms, such as the 'Rough and Tumble' or 'Kicking and Knocking' while the North was the epicenter of American prizefighting. Despite the training of the Southern gentlemen, the fights in their part of the world were not a reflection of English culture but rather, a fluid set of styles that reflected the men who practiced them. The 'Rough and Tumble' was the of the poor, white trappers and lumbermen who had zero regard for their own looks, and 'Kicking and Knocking' was the prevue of the African slave intent of maintaining some form of cultural continuity despite their circumstances in this new, strange country that both needed and despised them.As with any group of people who practiced a martial art historically, fighting sports function as a means of self-protection when a trained individual found himself or herself in dire circumstances. Many African slaves called upon their training when faced with atrocities to be perpetrated upon themselves or their family members. Stories of slaves fighting aggressive overseers populate nearly every slave narrative although, as Desch Obi notes, "given the oppressive nature of racial slavery, few could respond this way to every insult," but that many slaves simply "[drew] a line at physical violence."Women who were enslaved frequently put their cultural martial arts training to use in order to defend themselves, on all sides, from rape. Female slaves would practice wrestling as part of the ritual performance and contest, and those techniques were put to good use when faced with rape or brutality. Silvia Dubois, an African woman whose mistress routinely assaulted her, took her revenge by beating her mistress so severely that the white people who watched were so shocked that Silvia managed to flee her oppressor and escape her bonds.The results of slavery are far reaching and have a significant, lasting, and insidious impact on American culture today. There is a tendency to think of slavery as the complete dehumanization of the enslaved, but that misconception does not recognize the communities that, out of trauma and necessity, people create in order to maintain their humanity. Sharing traditions and customs across ethnic lines, and through generations, the African slave population in the American South retained a sense of self, both collective and individual. The collective trauma of slavery generated a need for African fighting arts to endure and to grow, and today the many styles of martial arts practiced in the U.S. and abroad contain elements of slave traditions, although they are not given their due credit. We often equate fighting sports to either European or Asian tradition, which ignores the vast history of martial arts across all peoples, even those that were subjugated and victimized.Fighting sports exist, currently and historically, in every culture, crossing boundaries of race, religion and gender, but we can never, and shall never forget, that the legacy of so many of our martial arts were formed out of necessity and created through the blood, the sweat, and the lives of those who came before us.

The slaves who did fight in the of English pugilism, especially in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, may have had more opportunity to change their circumstances, but the United States, even in the North, was not the ideal place for them to showcase their talents. As was revealed in last week's article on the Irish, Jewish, and African immigrant populations in England, African men had opportunities to fight and create careers for themselves in Britain, and so the few African American pugilists who succeeded in the U.S. found ways to move to England. Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux were both born slaves and after becoming free, moved to New York and then to England. It is unclear in the records just how both men went from slaves to freeman, despite conjecture that they earned it via their pugilistic endeavors. Richmond was a freeman before he was employed by the Duke of Northumberland and taken to England with his new master to work, on his own, as a cabinetmaker and a boxer. There are legends, completely unsubstantiated and embellished over time, that claim Molineaux won his freedom after his master won $100,000 in a bet on Tom's success, and a version of this could be true. The most important takeaway from both Richmond and Molineaux stories is that despite their dominance as pugilists in the United States, given the opportunity, they left as soon as they could for better lives in England. Even when African men and women were technically free in the United States, their lives were still harsh and tainted by racism and hatred in the country that neither they, nor their ancestors, would have chosen for their own.African boxers were not the only ones to set sail for England. White American pugilists also saw England as the preeminent location for aspiring champions and their departure, along with African fighters, left the United States bereft of some of the best talent. Meanwhile, those men and women still enslaved in the South sought to create their own fighting traditions, carved out of the customs of their ancestors. Fighting sports in enslaved populations in the United States functioned as ritual, as performance, and as communal bonding. The continuation of African traditions in their current, dire circumstances provided the African men and women with a chance to remember their history through song, dance, and sport.Certain fighting sports in the South were, interestingly, more of a creation of new, brutal forms, such as the 'Rough and Tumble' or 'Kicking and Knocking' while the North was the epicenter of American prizefighting. Despite the training of the Southern gentlemen, the fights in their part of the world were not a reflection of English culture but rather, a fluid set of styles that reflected the men who practiced them. The 'Rough and Tumble' was the of the poor, white trappers and lumbermen who had zero regard for their own looks, and 'Kicking and Knocking' was the prevue of the African slave intent of maintaining some form of cultural continuity despite their circumstances in this new, strange country that both needed and despised them.As with any group of people who practiced a martial art historically, fighting sports function as a means of self-protection when a trained individual found himself or herself in dire circumstances. Many African slaves called upon their training when faced with atrocities to be perpetrated upon themselves or their family members. Stories of slaves fighting aggressive overseers populate nearly every slave narrative although, as Desch Obi notes, "given the oppressive nature of racial slavery, few could respond this way to every insult," but that many slaves simply "[drew] a line at physical violence."Women who were enslaved frequently put their cultural martial arts training to use in order to defend themselves, on all sides, from rape. Female slaves would practice wrestling as part of the ritual performance and contest, and those techniques were put to good use when faced with rape or brutality. Silvia Dubois, an African woman whose mistress routinely assaulted her, took her revenge by beating her mistress so severely that the white people who watched were so shocked that Silvia managed to flee her oppressor and escape her bonds.The results of slavery are far reaching and have a significant, lasting, and insidious impact on American culture today. There is a tendency to think of slavery as the complete dehumanization of the enslaved, but that misconception does not recognize the communities that, out of trauma and necessity, people create in order to maintain their humanity. Sharing traditions and customs across ethnic lines, and through generations, the African slave population in the American South retained a sense of self, both collective and individual. The collective trauma of slavery generated a need for African fighting arts to endure and to grow, and today the many styles of martial arts practiced in the U.S. and abroad contain elements of slave traditions, although they are not given their due credit. We often equate fighting sports to either European or Asian tradition, which ignores the vast history of martial arts across all peoples, even those that were subjugated and victimized.Fighting sports exist, currently and historically, in every culture, crossing boundaries of race, religion and gender, but we can never, and shall never forget, that the legacy of so many of our martial arts were formed out of necessity and created through the blood, the sweat, and the lives of those who came before us.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement