Photos by Perry Nelson-USA TODAY Sports, Tom Szczerbowski-USA TODAY Sports

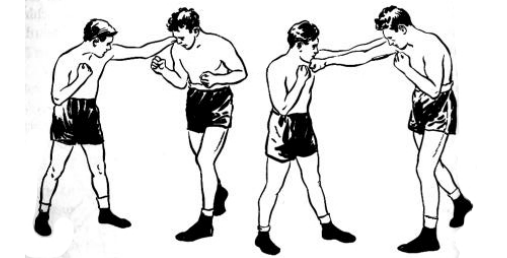

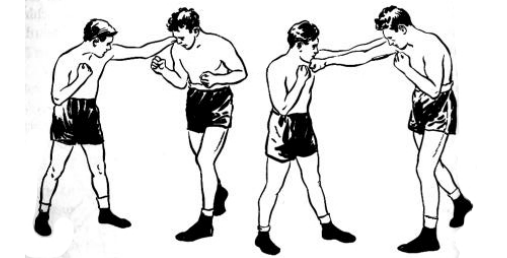

For the second time in the past few years, South Korea’s mandatory military service laws are a hot topic in mixed martial arts. In 2013, Chan Sung Jung—a great finisher with his fists, knees and submissions—was riding a three-fight winning streak in the UFC featherweight division when he got thrown into a title fight with the great Jose Aldo. After injuring himself in that fight, Jung took some time off before announcing his intention to fulfill his military service in 2014. Jung returned to the cage in February 2017. Next in line is Doo Ho Choi.A thunderous puncher who became a fan favorite within his first two UFC bouts, Choi declared earlier this week that he desires a title shot before he begins his mandatory service. It would certainly be fascinating to see what kind of case a UFC title could make, and the idea isn't too far-fetched. Olympic and Asian Games medalists have been allowed to complete a few weeks of basic training and return to their athletic careers, while the South Korean air force used to have an elite StarCraft team to keep the country's top gamers in action.A run at the title inside 2018 seems like a long shot for Choi, though. After riding a wave of momentum after three first-round knockouts in the UFC, he was handed a punishing loss in his most recent bout against the grizzled veteran Cub Swanson. It was a fight-of-the-year candidate and both men took a beating, but it did more harm to the unstoppable aura of Choi, who, as Swanson’s team famously asserted, couldn’t fight while backing up.This weekend, Choi meets one of the UFC’s longest-serving featherweights, Jeremy Stephens, in what is predictably being booked as a "he who lands first, wins" kind of match.The Cross Counter and the Inside RightA right straight didn’t used to be "the cross." The cross referred to "crossing" an opponent’s straight blow. He jabs, you slip inside and throw your right hand across the top. Could be an overhand, could be a slightly curving straight blow, but if it connects on the temple or jawline as he is extending, it has a great chance of sending him reeling. The overhand is the most common punch in MMA and in many cases the least effective, but time it so that it is crossing the opponent’s jab and you might just have a one-punch knockout on your hands.The inside right you will see less often. Here is the great Edwin Haislet’s description from Boxing:“As the opponent leads a left jab, quickly turn the body to the left, bringing the right shoulder forward to the center line. From this point drive the right hand into complete extension. The left lead slips to the outside of the right arm. The left hand is held in the position of guard. A short step to the left, shifting the weight over a straight left leg may be used to obtain more power.” While both the cross counter and the inside right involve slipping to the left, you will notice that the inside right, as Haislet shows it, requires the fighter to get his right shoulder inside of the opponent’s left. This slight angle creates the ideal line for the right straight, and you will see fighters set up the same line when using the left hook to line up a right straight.This brings us to Doo Ho Choi’s peculiar right hand. Part straight, part overhand, part cross, and part inside right. Notice how whenever Choi throws his right hand, he leans well off to his left and often his right shoulder is considerably higher than his left. Sometimes he’ll throw what looks like a straight punch, extending at the elbow, but where Haislet’s inside right has the counter-fighter’s elbow tight to the ribs, Choi’s elbow will be the highest point on his body. Timing his right hand over the top of his opponent’s left, or down the inside of it, Choi has scored a number of remarkable knockouts.The problems come when the exchange goes beyond the first punch. While Choi is capable of showing tighter control of his balance—as on the right straight that put down Thiago Tavares—more often he is working on the counter and throws all of his weight onto his lead leg as soon as he thinks he can land. This leaning right hand leaves him off balance and slow to either return to his stance or come back with the left hook. Cub Swanson did well getting the better of Choi in longer exchanges and trades.Notice how much of Choi’s weight is ahead of his lead leg and how far he is leaning forward of his hips.Choi’s left hook is decently powerful, too, and he hurt Sam Sicilia with it, but the lag time between his right hand and his left hook is considerable. A catch-and-pitch left hook would likely cause Choi all kinds of trouble. A nice example of this idea came at K-1’s recent heavyweight grand prix (yes, they actually are still doing those). "Mr. Cool" Ibrahim El Bouni starched his quarter- and semi-final opponents with his left hook after opening a flurry with his right hand. He hurt Antonio Plazibat with it in the final, until Plazibat decided to put his guard up, take the first punch that El Bouni threw on his guard, and use that as his trigger to fire back with the left hook. After clipping El Bouni a couple of times, Plazibat had the Moroccan knockout artist afraid to open up and was able to work more confidently to secure a decision victory.However one-note Choi’s offense, his timing and power have proven enough to take out a number of passable featherweight talents. This makes him an interesting contrast to his opponent—a man who has all the power in the world, a lot of different looks, and who still cannot consistently stop his opponents.Knockout Artistry and the Low, Low KickJeremy Stephens is a bizarre fighter. He’s still marketed as a knockout artist even though his knockout percentage is mediocre, scoring just four in the last decade. Like Rashad Evans, Stephens' two key knockouts are played on repeat to create a hype package for UFC events—the mileage they have gotten out of that uppercut against Rafael dos Anjos in 2008 is quite astounding. In 25 fights with the UFC, he has scored just seven knockouts in total. He also has a habit of seeming like he’s finally "gotten it together," putting on a blinder against a decent opponent, and then looking completely out of place in his next fight.After a decision loss to now-champ Max Holloway in December 2016, Stephens looked better than he ever had before when he welcomed Renan Barao to featherweight. A loss to the brilliant Frankie Edgar followed, but then Stephens—as the No. 5 ranked featherweight in the world—took on the unranked Renato Moicano. Stephens looked absolutely baffled as the Brazilian circled away from him, kicking and denying exchanges, and timing takedowns when Stephens overcommitted to the chase. Most recently, Stephens met a returning Gilbert Melendez—once considered a lightweight great—and battered him up and down after hobbling his leg in the first round.Watching Stephens fight, it becomes apparent that he might do better if all his matches were fought in a parking space. As soon as his opponent starts moving, he is lost.One trick that Stephens has picked up in recent years, and which subsequently appeared on every UFC card of 2017, is the low, low kick. To see the value of kicking below the knee, consider what the main dangers are in kicking the leg to begin with. When kicking the thigh, all the opponent needs do is set his weight and bend the lead leg into the kick and the kicker’s shin will ride up into his hip pocket, ready for the takedown.Mirko "Cro Cop" Filipovic has aptly described another downside. When he was asked why he didn’t throw low kicks, Cro Cop pointed out that it only takes one good high kick or body kick to finish a fight, but it only takes one bad low kick to crack a bone and be significantly handicapped for the rest of the fight. Where broken low kicks on checks are still considered freak accidents by some, they happen to even elite kickboxers when they mistime their kicks.The nature of checking low kicks is that the higher on the shin you take them, the less of the kick you will feel and the more it is going to hurt your opponent. In training, many good kickboxers will exaggerate their checks, lifting their check high and taking kicks on the middle of the shin even when wearing shin pads, but come fight time a little raise and turn is all it takes to place the hardest part of the leg directly into the opponent’s mid-to-lower shin.You can do check a kick by picking up the lead leg, or even just by getting onto the ball of the foot and turning the shin out if you’re feeling very economical. You can’t, however, lower your leg if the opponent decides to kick low. When a fighter kicks below the knee, he is almost guaranteed to avoid the worst of it. So essentially, fighters are now choosing a guaranteed-to-be-rough shin-on-shin connection—ideally the side of the shin or even the calf—instead of a riskier shot at the tender meat of the thigh.There doesn’t yet seem to be a decent way to check a low, low kick. The best means of dealing with it is, as with low line straight kicks, to withdraw the leg and move in through the wake of the kick. Raising the leg to check the low, low kick simply allows the opponent to kick the more sensitive lower shin, as it flaps on the end of a lever.When Stephens had Melendez standing in front of him, he worked very well in combinations and searched for as many body shots and low kicks as he did home-run uppercuts and swings. It seems unlikely that this late in his career Stephens will tighten everything up and become the perfect technician, but we do seem to be a good distance removed from the guy who went charging chin first after Yves Edwards and got laid out with check hooks.Hypothetical Game PlansFor Stephens, it is probably worth going after Choi’s lead leg, but Choi isn’t a very laterally mobile fighter anyway. He's more into a long stance and linear movement. That could pair very well with Stephens’ low kicks, but Choi is always waiting to step down the center with his right hand. It doesn’t matter how hard the kick connects if you eat a stiff right hand while you’re on one leg. Feints are not a regular fixture in the Jeremy Stephens toolbox, but against a man who is waiting on a hair trigger to drop the right hand—and who throws himself out of position so completely when he does—feints would be an invaluable weapon. Feinting Choi into throwing would make landing the low kicks far easier as he retreated from his missed counter into his stance, and if Choi’s finger comes off the trigger after a few feints, Stephens can step in and get more aggressive.Stephens’ body work is actually very good. If he went to it more there is a good chance he’d pick up more finishes. Against such a one-trick counter puncher, this would be the perfect fight to pull out the jab-and-duck, initiating an exchange only to drop under Choi’s punches and begin hammering the body. With Choi’s right flank so completely exposed for such a lengthy period after his right hand, the left hook to the liver could be a killer.The great example we always use to illustrate the jab-and-duck is Roberto Duran. He could get in, hit the body, and get out like nobody in the game. It all stemmed from using the jab as the trigger for his opponent’s counters, and already being in motion when he started firing. And of course it doesn’t have to be a duck. You can slip anyway you want as long as you’re not where the opponent thought you were going to be.Choi’s takedown defense has only been tested a little in the UFC. Cub Swanson was able to mount him and give him trouble on the ground, but the two had exchanged a few headache-makers at that point. Should Stephens find himself struggling with Choi's speed, pushing the fight to the fence and making a grind of it might be a good idea, and one he should go to earlier rather than later in order to reap the benefits. Pushing off out of the clinch and looking to land low kicks along the fence is an underused strategy. It's part of what makes Justin Gaethje so dangerous, and it could serve Stephens well here.For Choi, now would be the time to apply some lateral movement, because it makes fighting Stephens so much easier. If Stephens is constantly moving and turning, he cannot wind his punches up behind him. Furthermore, his impatience can lead to him walking in completely square, making for easy takedowns or, more appropriately, giving Choi the chance to shoot a straight tight up the center.Choi feigns the jab in every single fight but rarely ever throws it. Stephens has added some neater counter punches to his game in recent years, but he will move his head the first punch that his opponent shows him. This is where the jab is so useful for a good boxer—it is a flicking, noncommittal blow that makes the opponent show his intentions before the jabber ever has to open up. Jabbing Stephens into pulling his head back for the pull right hand that he has used recently would leave him in dire straits should Choi’s right hand follow.One important point in this fight for Choi is to stay off the fence. Stephens is no Rafael dos Anjos; he isn’t going to mercilessly take advantage of every moment along the fence, and in fact he let Renato Moicano escape while awkwardly trying to find a swing at his head, but he will still go for broke if he sees his man hit the fence.This is a peculiar main event. Choi is looking to rebound and regain some momentum, but aside from Yves Edwards in 2012, Stephens has never been knocked out—and that Edwards knockout was more Stephens’ aggression and Edwards’ timing than Edwards’ power or Stephens’ chin. If Stephens has proved anything in his lengthy, hot-and-cold career, it is that he can take a licking and keep on ticking. Choi has gone the distance once since 2011, and that was the loss against Cub Swanson. For all his swinging for the fences, Stephens doesn’t seem to lose heart when he can’t get the knockout. For a young, highly touted knockout artist like Choi, though, that is a very real possibility.Jack wrote the hit biography Notorious: The Life and Fights of Conor McGregor and scouts prospects at The Fight Primer .

While both the cross counter and the inside right involve slipping to the left, you will notice that the inside right, as Haislet shows it, requires the fighter to get his right shoulder inside of the opponent’s left. This slight angle creates the ideal line for the right straight, and you will see fighters set up the same line when using the left hook to line up a right straight.This brings us to Doo Ho Choi’s peculiar right hand. Part straight, part overhand, part cross, and part inside right. Notice how whenever Choi throws his right hand, he leans well off to his left and often his right shoulder is considerably higher than his left. Sometimes he’ll throw what looks like a straight punch, extending at the elbow, but where Haislet’s inside right has the counter-fighter’s elbow tight to the ribs, Choi’s elbow will be the highest point on his body. Timing his right hand over the top of his opponent’s left, or down the inside of it, Choi has scored a number of remarkable knockouts.The problems come when the exchange goes beyond the first punch. While Choi is capable of showing tighter control of his balance—as on the right straight that put down Thiago Tavares—more often he is working on the counter and throws all of his weight onto his lead leg as soon as he thinks he can land. This leaning right hand leaves him off balance and slow to either return to his stance or come back with the left hook. Cub Swanson did well getting the better of Choi in longer exchanges and trades.Notice how much of Choi’s weight is ahead of his lead leg and how far he is leaning forward of his hips.Choi’s left hook is decently powerful, too, and he hurt Sam Sicilia with it, but the lag time between his right hand and his left hook is considerable. A catch-and-pitch left hook would likely cause Choi all kinds of trouble. A nice example of this idea came at K-1’s recent heavyweight grand prix (yes, they actually are still doing those). "Mr. Cool" Ibrahim El Bouni starched his quarter- and semi-final opponents with his left hook after opening a flurry with his right hand. He hurt Antonio Plazibat with it in the final, until Plazibat decided to put his guard up, take the first punch that El Bouni threw on his guard, and use that as his trigger to fire back with the left hook. After clipping El Bouni a couple of times, Plazibat had the Moroccan knockout artist afraid to open up and was able to work more confidently to secure a decision victory.However one-note Choi’s offense, his timing and power have proven enough to take out a number of passable featherweight talents. This makes him an interesting contrast to his opponent—a man who has all the power in the world, a lot of different looks, and who still cannot consistently stop his opponents.Knockout Artistry and the Low, Low KickJeremy Stephens is a bizarre fighter. He’s still marketed as a knockout artist even though his knockout percentage is mediocre, scoring just four in the last decade. Like Rashad Evans, Stephens' two key knockouts are played on repeat to create a hype package for UFC events—the mileage they have gotten out of that uppercut against Rafael dos Anjos in 2008 is quite astounding. In 25 fights with the UFC, he has scored just seven knockouts in total. He also has a habit of seeming like he’s finally "gotten it together," putting on a blinder against a decent opponent, and then looking completely out of place in his next fight.After a decision loss to now-champ Max Holloway in December 2016, Stephens looked better than he ever had before when he welcomed Renan Barao to featherweight. A loss to the brilliant Frankie Edgar followed, but then Stephens—as the No. 5 ranked featherweight in the world—took on the unranked Renato Moicano. Stephens looked absolutely baffled as the Brazilian circled away from him, kicking and denying exchanges, and timing takedowns when Stephens overcommitted to the chase. Most recently, Stephens met a returning Gilbert Melendez—once considered a lightweight great—and battered him up and down after hobbling his leg in the first round.Watching Stephens fight, it becomes apparent that he might do better if all his matches were fought in a parking space. As soon as his opponent starts moving, he is lost.One trick that Stephens has picked up in recent years, and which subsequently appeared on every UFC card of 2017, is the low, low kick. To see the value of kicking below the knee, consider what the main dangers are in kicking the leg to begin with. When kicking the thigh, all the opponent needs do is set his weight and bend the lead leg into the kick and the kicker’s shin will ride up into his hip pocket, ready for the takedown.Mirko "Cro Cop" Filipovic has aptly described another downside. When he was asked why he didn’t throw low kicks, Cro Cop pointed out that it only takes one good high kick or body kick to finish a fight, but it only takes one bad low kick to crack a bone and be significantly handicapped for the rest of the fight. Where broken low kicks on checks are still considered freak accidents by some, they happen to even elite kickboxers when they mistime their kicks.The nature of checking low kicks is that the higher on the shin you take them, the less of the kick you will feel and the more it is going to hurt your opponent. In training, many good kickboxers will exaggerate their checks, lifting their check high and taking kicks on the middle of the shin even when wearing shin pads, but come fight time a little raise and turn is all it takes to place the hardest part of the leg directly into the opponent’s mid-to-lower shin.You can do check a kick by picking up the lead leg, or even just by getting onto the ball of the foot and turning the shin out if you’re feeling very economical. You can’t, however, lower your leg if the opponent decides to kick low. When a fighter kicks below the knee, he is almost guaranteed to avoid the worst of it. So essentially, fighters are now choosing a guaranteed-to-be-rough shin-on-shin connection—ideally the side of the shin or even the calf—instead of a riskier shot at the tender meat of the thigh.There doesn’t yet seem to be a decent way to check a low, low kick. The best means of dealing with it is, as with low line straight kicks, to withdraw the leg and move in through the wake of the kick. Raising the leg to check the low, low kick simply allows the opponent to kick the more sensitive lower shin, as it flaps on the end of a lever.When Stephens had Melendez standing in front of him, he worked very well in combinations and searched for as many body shots and low kicks as he did home-run uppercuts and swings. It seems unlikely that this late in his career Stephens will tighten everything up and become the perfect technician, but we do seem to be a good distance removed from the guy who went charging chin first after Yves Edwards and got laid out with check hooks.Hypothetical Game PlansFor Stephens, it is probably worth going after Choi’s lead leg, but Choi isn’t a very laterally mobile fighter anyway. He's more into a long stance and linear movement. That could pair very well with Stephens’ low kicks, but Choi is always waiting to step down the center with his right hand. It doesn’t matter how hard the kick connects if you eat a stiff right hand while you’re on one leg. Feints are not a regular fixture in the Jeremy Stephens toolbox, but against a man who is waiting on a hair trigger to drop the right hand—and who throws himself out of position so completely when he does—feints would be an invaluable weapon. Feinting Choi into throwing would make landing the low kicks far easier as he retreated from his missed counter into his stance, and if Choi’s finger comes off the trigger after a few feints, Stephens can step in and get more aggressive.Stephens’ body work is actually very good. If he went to it more there is a good chance he’d pick up more finishes. Against such a one-trick counter puncher, this would be the perfect fight to pull out the jab-and-duck, initiating an exchange only to drop under Choi’s punches and begin hammering the body. With Choi’s right flank so completely exposed for such a lengthy period after his right hand, the left hook to the liver could be a killer.The great example we always use to illustrate the jab-and-duck is Roberto Duran. He could get in, hit the body, and get out like nobody in the game. It all stemmed from using the jab as the trigger for his opponent’s counters, and already being in motion when he started firing. And of course it doesn’t have to be a duck. You can slip anyway you want as long as you’re not where the opponent thought you were going to be.Choi’s takedown defense has only been tested a little in the UFC. Cub Swanson was able to mount him and give him trouble on the ground, but the two had exchanged a few headache-makers at that point. Should Stephens find himself struggling with Choi's speed, pushing the fight to the fence and making a grind of it might be a good idea, and one he should go to earlier rather than later in order to reap the benefits. Pushing off out of the clinch and looking to land low kicks along the fence is an underused strategy. It's part of what makes Justin Gaethje so dangerous, and it could serve Stephens well here.For Choi, now would be the time to apply some lateral movement, because it makes fighting Stephens so much easier. If Stephens is constantly moving and turning, he cannot wind his punches up behind him. Furthermore, his impatience can lead to him walking in completely square, making for easy takedowns or, more appropriately, giving Choi the chance to shoot a straight tight up the center.Choi feigns the jab in every single fight but rarely ever throws it. Stephens has added some neater counter punches to his game in recent years, but he will move his head the first punch that his opponent shows him. This is where the jab is so useful for a good boxer—it is a flicking, noncommittal blow that makes the opponent show his intentions before the jabber ever has to open up. Jabbing Stephens into pulling his head back for the pull right hand that he has used recently would leave him in dire straits should Choi’s right hand follow.One important point in this fight for Choi is to stay off the fence. Stephens is no Rafael dos Anjos; he isn’t going to mercilessly take advantage of every moment along the fence, and in fact he let Renato Moicano escape while awkwardly trying to find a swing at his head, but he will still go for broke if he sees his man hit the fence.This is a peculiar main event. Choi is looking to rebound and regain some momentum, but aside from Yves Edwards in 2012, Stephens has never been knocked out—and that Edwards knockout was more Stephens’ aggression and Edwards’ timing than Edwards’ power or Stephens’ chin. If Stephens has proved anything in his lengthy, hot-and-cold career, it is that he can take a licking and keep on ticking. Choi has gone the distance once since 2011, and that was the loss against Cub Swanson. For all his swinging for the fences, Stephens doesn’t seem to lose heart when he can’t get the knockout. For a young, highly touted knockout artist like Choi, though, that is a very real possibility.Jack wrote the hit biography Notorious: The Life and Fights of Conor McGregor and scouts prospects at The Fight Primer .

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement